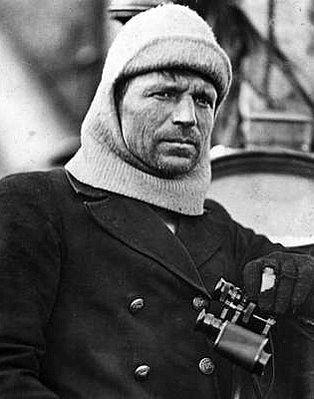

Frank Arthur Worsley (1872 - 1943)

Biographical notes

Captain of the

Endurance

1914-17 - 42 at the start of the expedition

Hydrography,

sailing master

Quest-

Ernest Shackleton 1921 - 1922

The

Endurance Expedition

The

Endurance Expedition

Frank Worsley was pleasingly possessed of some eccentricities - claiming that his cabin was too stuffy, for instance, and sleeping every night on the passageway floor.

In the 1931 book "Endurance" he writes:

-

"One night I dreamed that Burlington

Street was full of ice blocks and that I was navigating

a ship along it. Next morning I awoke and hurried along

to Burlington Street. A sign on a door caught my eye. It

bore the words "Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition". I

turned into the building, Shackleton was there, and after

a few minutes conversation he announced "Your Engaged"

In 1914 at the age of 42, he joined Shackleton's 1914-17 "Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition" as the master of the Endurance, the expedition ship. As a captain of a ship however, his skills were somewhat stretched, by the time Shackleton joined the ship at South America, Worsley was effectively made second in command due to his ineffective handling of indiscipline and inappropriate behaviour in the crew. True to form however, this was handled diplomatically by Shackleton and effectively played down, Worsley would move than prove his worth later in the expedition.

When the Endurance was lost, crushed by the pack ice in the Weddell Sea, Worsley took charge of one of the lifeboats, the Dudley Docker and guided the crew towards a distant speck on the far distant and unseen speck on the horizon that was Elephant Island. Shortly after arriving on Elephant Island, Worsley accompanied Shackleton and a small party on another lifeboat, the James Caird on a sixteen day journey to South Georgia to fetch help for the rest of the men stranded on Elephant Island.

This was a remarkable feat of navigation as well as of seamanship and perseverance by the men. Worsley was only able to take a navigational reading every few days due to weather conditions, a small error would have meant the James Caird heading into open ocean with no hope of rescue for anyone.

Biography

Shackleton's Boat Journey: The narrative of Frank Worsley Buy |

Frank Worsley was a New Zealander, born in Akaroa. He became an apprentice to the merchant navy at the age of 15 serving on both sailing and steam ships.

He returned to sea after the Endurance expedition, commanding "Q boats" in the First World War - anti-submarine boats disguised as merchant shipping. He was twice decorated for anti-submarine action, once with the D.S.O.

Worsley, known to his intimates as Depth-Charge Bill, owing to his success with that particular method of destroying German submarines, has the Distinguished Service Order and three submarines to his credit.

Worsley became part of the North Russia Expeditionary Force at the request of Shackleton In late October 1918. This was an Endurance reunion as Shackleton, Wild , Macklin, Hussey and McIlroy were also part of the same force. Worsley won the D.S.O. for the second time for leading a daring land raid against the Bolsheviks.

Shackleton from "South":

On my return, after the rescue of the survivors of the Ross Sea Party, I offered my services to the Government, and was sent on a mission to South America. When this was concluded I was commissioned as Major and went to North Russia in charge of Arctic Equipment and Transport, having with me Worsley, Stenhouse, Hussey, Macklin, and Brocklehurst, who was to have come South with us, but who, as a regular officer, rejoined his unit on the outbreak of war. He has been wounded three times and was in the retreat from Mons. Worsley was sent across to the Archangel front, where he did excellent work, and the others served with me on the Murmansk front. The mobile columns there had exactly the same clothing, equipment, and sledging food as we had on the Expedition. No expense was spared to obtain the best of everything for them, and as a result not a single case of avoidable frost-bite was reported.

After the war, Worsley was involved in Shackleton's last expedition on the Quest, cut short by Shackleton's death on South Georgia. Like Shackleton, Worsley was bad with his own finances and for several years earned money by giving lectures about the Endurance expedition, he commentated on Shackleton's film "South" released in 1919.

In 1925 he became joint leader of an Arctic expedition to Franz Josef Land and in 1935 was part of a treasure hunting expedition in the Cocos Islands.

Despite retiring from the sea in 1939, he remained a Royal naval reserve officer and continued to instruct at the Royal Naval College in Greenwich until his death in 1943. He had secured a job on a merchant ship called the "Dalriada" working at Sheerness in 1941 by lying about his age, he claimed to be just 65, when he really was 70!, unfortunately he lost the job once found out.

He died of cancer of the lung in February 1943, just a few days after diagnosis. His was cremation at Woking and the memorial service at Greenwich College Chapel was as grand an affair as would expected for someone with Worsley's maritime history. His ashes were scattered at sea near the mouth of the River Thames.

References to Frank Worsley by Orde-Lees in "Elephant Island and Beyond" buy USA buy UK

-

Another beautiful day, though nearly so light as yesterday. There was much pressure going on , so Captain Worsley and Clarke went over to watch it. Captain Worsley is our skipper. He is a vital spark. His activity and keenness are extraordinary. In accidentally wintering here he is achieving a lifelong ambition. I am sure he must be an invaluable helpmate to Sir Ernest.

A New Zealander by birth, he is of Yorkshire extraction. About 44 years of age, he looks ever so much younger and is far more nimble than most men half his age. Although some fellows are a little inclined to chaff him rather uncharitably about his little whims, his excess of zeal and his over-anxiety to make sensational discoveries, yet there is no doubt that everyone recognises his undoubted suitability fo the post he holds.

Personally I have always found him a sound counselor and a firm friend and I have a great respect for him, but it must be admitted that some of our members are experiencing submission to discipline for the first time and do not perhaps realise its advantages quite so easily as those of us who have spent a good many years in H.M. service.

The skippers's principal whims were his eagerness to announce at every port at which we touched on the way out that this was "Sir Ernest Shackleton's flag ship Endurance bound for the Antarctic on a voyage of discovery", and his persistence in declaring that the cabins etc. on board are stuffy that he has to sleep outside in the passages, which is what he actually does : but he is very much "all there" in spite of these quaint little peculiarities, and after all who has not their own idiosyncrasies when one comes to examine ones self. -

Lately I have taken in hand the hairless pates of our skipper and another member, rubbing Vaseline into them and massaging them for five to 10 minutes nightly. It is too early to report results. Last night I was prepared to "do" the skipper. Captain Worsley, but as he was not ready I sat down and read for a while. Presently he said , "Now then colonel, if you'll be so good", and so up I got and put down my book and went across to him. At that moment someone came in with whom the skipper engaged himself in conversation for several minutes, and then dived into the nautical almanac for another period of several minutes.

With that, and my hands all vaseliney, I got all huffy, slammed the Vaseline tin with a snap, wiped my hands on the captains spotlessly clean towel, and resumed my book, "Words" began to pass between us , and the situation became a little strained , but fortunately before we reached the stage of an interchange of nomenclature we both saw the humour of the situation, be it said to our lasting credit, and although he would not thereafter permit me to rub his bald spot, nor I condescended to do it, we parted amicably and wished each other the customary cordial "good night". -

Captain Worsley in the Dudley Docker, too stuck to his post gallantly hour by hour, steering his boat skillfully to safety, sitting up in the stern wet through to the skin. Lt. Hudson and Crean, who steered the Stancomb Wills alternately, are likewise deserving of the highest praise.

References to Frank Worsley in Shackleton's book "South!" buy USA buy UK

- The situation became dangerous that night. We pushed

into the pack in the hope of reaching open water beyond,

and found ourselves after dark in a pool which was growing

smaller and smaller. The ice was grinding around the ship

in the heavy swell, and I watched with some anxiety for

any indication of a change of wind to the east, since a

breeze from that quarter would have driven us towards the

land. Worsley and I were on deck all night,

dodging the pack. At 3 a.m. we ran south, taking advantage

of some openings that had appeared, but met heavy rafted

pack-ice, evidently old; some of it had been subjected to

severe pressure.

- A lizard-like head would show while the killer gazed

along the floe with wicked eyes. Then the brute would dive,

to come up a few moments later, perhaps, under some unfortunate

seal reposing on the ice. Worsley examined

a spot where a killer had smashed a hole 8 ft. by 12 ft.

in 12 and a half in. of hard ice, covered by 2 and a half

in. of snow. Big blocks of ice had been tossed on to the

floe surface. Wordie, engaged in measuring the thickness

of young ice, went through to his waist one day just as

a killer rose to blow in the adjacent lead. His companions

pulled him out hurriedly.

- Worsley took a party to the floe on

the 26th and started building a line of igloos and "dogloos"

round the ship. These little buildings were constructed,

Esquimaux fashion, of big blocks of ice, with thin sheets

for the roofs. Boards or frozen sealskins were placed over

all, snow was piled on top and pressed into the joints,

and then water was thrown over the structures to make everything

firm. The ice was packed down flat inside and covered with

snow for the dogs, which preferred, however, to sleep outside

except when the weather was extraordinarily severe. The

tethering of the dogs was a simple matter. The end of a

chain was buried about eight inches in the snow, some fragments

of ice were pressed around it, and a little water poured

over all. The icy breath of the Antarctic cemented it in

a few moments.

- I took the ship back over our course for four miles,

to a point where some looser pack gave faint promise of

a way through; but, after battling for three hours with

very heavy hummocked ice and making four miles to the south,

we were brought up by huge blocks and floes of very old

pack. Further effort seemed useless at that time, and I

gave the order to bank fires after we had moored the Endurance

to a solid floe. The weather was clear, and some enthusiastic

football-players had a game on the floe until, about midnight,

Worsley dropped through a hole in rotten

ice while retrieving the ball. He had to be retrieved himself.

- The Endurance made some progress on the following day.

Long leads of open water ran towards the south-west, and

the ship smashed at full speed through occasional areas

of young ice till brought up with a heavy thud against a

section of older floe. Worsley was out

on the jib-boom end for a few minutes while Wild was conning

the ship, and he came back with a glowing account of a novel

sensation. The boom was swinging high and low and from side

to side, while the massive bows of the ship smashed through

the ice, splitting it across, piling it mass on mass and

then shouldering it aside. The air temperature was 37° Fahr.,

pleasantly warm, and the water temperature 29° Fahr.

- "Since noon the character of the pack has improved,"

wrote Worsley on this day. "Though the

leads are short, the floes are rotten and easily broken

through if a good place is selected with care and judgment.

In many cases we find large sheets of young ice through

which the ship cuts for a mile or two miles at a stretch.

I have been conning and working the ship from the crow's-nest

and find it much the best place, as from there one can see

ahead and work out the course beforehand, and can also guard

the rudder and propeller, the most vulnerable parts of a

ship in the ice. At midnight, as I was sitting in the

tub' I heard a clamorous noise down on the deck, with ringing

of bells, and realized that it was the New Year."

Worsley came down from his lofty seat and

met Wild, Hudson, and myself on the bridge, where we shook

hands and wished one another a happy and successful New

Year. Since entering the pack on December 11 we had come

480 miles, through loose and close pack-ice.

- The two subjects of most interest to us were our rate

of drift and the weather. Worsley took

observations of the sun whenever possible, and his results

showed conclusively that the drift of our floe was almost

entirely dependent upon the winds and not much affected

by currents. Our hope, of course, was to drift northwards

to the edge of the pack and then, when the ice was loose

enough, to take to the boats and row to the nearest land.

We started off in fine style, drifting north about twenty

miles in two or three days in a howling south-westerly blizzard.

- The increasing sea made it necessary for us to drag

the boats farther up the beach. This was a task for all

hands, and after much labour we got the boats into safe

positions among the rocks and made fast the painters to

big boulders. Then I discussed with Wild and Worsley

the chances of reaching South Georgia before the

winter locked the seas against us. Some effort had to be

made to secure relief. Privation and exposure had left their

mark on the party, and the health and mental condition of

several men were causing me serious anxiety. Blackborow's

feet, which had been frost-bitten during the boat journey,

were in a bad way, and the two doctors feared that an operation

would be necessary.

- The case required to be argued in some detail, since

all hands knew that the perils of the proposed journey were

extreme. The risk was justified solely by our urgent need

of assistance. The ocean south of Cape Horn in the middle

of May is known to be the most tempestuous storm-swept area

of water in the world. The weather then is unsettled, the

skies are dull and overcast, and the gales are almost unceasing.

We had to face these conditions in a small and weather-beaten

boat, already strained by the work of the months that had

passed. Worsley and Wild realized that

the attempt must be made, and they both asked to be allowed

to accompany me on the voyage. I told Wild at once that

he would have to stay behind. I relied upon him to hold

the party together while I was away and to make the best

of his way to Deception Island with the men in the spring

in the event of our failure to bring help. Worsley

II would take with me, for I had a very high opinion

of his accuracy and quickness as a navigator, and especially

in the snapping and working out of positions in difficult

circumstances ÂÂÂÂan opinion that was only

enhanced during the actual journey. Four other men would

be required, and I decided to call for volunteers, although,

as a matter of fact, I pretty well knew which of the people

I would select. Crean I proposed to leave on the island

as a right-hand man for Wild, but he begged so hard to be

allowed to come in the boat that, after consultation with

Wild, I promised to take him. I called the men together,

explained my plan, and asked for volunteers. Many came forward

at once. Some were not fit enough for the work that would

have to be done, and others would not have been much use

in the boat since they were not seasoned sailors, though

the experiences of recent months entitled them to some consideration

as seafaring men. McIlroy and Macklin were both anxious

to go but realized that their duty lay on the island with

the sick men. They suggested that I should take Blackborow

in order that he might have shelter and warmth as quickly

as possible, but I had to veto this idea. It would be hard

enough for fit men to live in the boat. Indeed, I did not

see how a sick man, lying helpless in the bottom of the

boat, could possibly survive in the heavy weather we were

sure to encounter. I finally selected McNeish, McCarthy,

and Vincent in addition to Worsley and

Crean. The crew seemed a strong one, and as I looked at

the men I felt confidence increasing.

- The decision made, I walked through the blizzard with

Worsley and Wild to examine the James Caird.

The 20-ft. boat had never looked big; she appeared to have

shrunk in some mysterious way when I viewed her in the light

of our new undertaking. She was an ordinary ship's whaler,

fairly strong, but showing signs of the strains she had

endured since the crushing of the Endurance.

- The weather was fine on April 23, and we hurried forward

our preparations. It was on this day I decided finally that

the crew for the James Caird should consist of Worsley,

Crean, McNeish, McCarthy, Vincent, and myself. A storm came

on about noon, with driving snow and heavy squalls. Occasionally

the air would clear for a few minutes, and we could see

a line of pack-ice, five miles out, driving across from

west to east. This sight increased my anxiety to get away

quickly. Winter was advancing, and soon the pack might close

completely round the island and stay our departure for days

or even for weeks, I did not think that ice would remain

around Elephant Island continuously during the winter, since

the strong winds and fast currents would keep it in motion.

We had noticed ice and bergs, going past at the rate of

four or five knots. A certain amount of ice was held up

about the end of our spit, but the sea was clear where the

boat would have to be launched.

- Worsley, Wild, and I climbed to the

summit of the seaward rocks and examined the ice from a

better vantage-point than the beach offered. The belt of

pack outside appeared to be sufficiently broken for our

purposes, and I decided that, unless the conditions forbade

it, we would make a start in the James Caird on the following

morning. Obviously the pack might close at any time. This

decision made, I spent the rest of the day looking over

the boat, gear, and stores, and discussing plans with

Worsley and Wild.

- The wind dropped, the snow-squalls became less

frequent, and the sea moderated. When the morning of the

seventh day dawned there was not much wind. We shook the

reef out of the sail and laid our course once more for South

Georgia. The sun came out bright and clear, and presently

Worsley got a snap for longitude. We hoped

that the sky would remain clear until noon, so that we could

get the latitude. We had been six days out without an observation,

and our dead reckoning naturally was uncertain.

- We revelled in the warmth of the sun that day. Life

was not so bad, after all. We felt we were well on our way.

Our gear was drying, and we could have a hot meal in comparative

comfort. The swell was still heavy, but it was not breaking

and the boat rode easily. At noon Worsley

balanced himself on the gunwale and clung with one hand

to the stay of the mainmast while he got a snap of the sun.

The result was more than encouraging. We had done over 380

miles and were getting on for half-way to South Georgia.

It looked as though we were going to get through.

- On the tenth night Worsley could not

straighten his body after his spell at the tiller. He was

thoroughly cramped, and we had to drag him beneath the decking

and massage him before he could unbend himself and get into

a sleeping-bag.

- We found that a big hole had been burned in the bottom

of Worsley's reindeer sleeping-bag during

the night. Worsley had been awakened by

a burning sensation in his feet, and had asked the men near

him if his bag was all right; they looked and could see

nothing wrong. We were all superficially frostbitten about

the feet, and this condition caused the extremities to burn

painfully, while at the same time sensation was lost in

the skin. Worsley thought that the uncomfortable

heat of his feet was due to the frost-bites, and he stayed

in his bag and presently went to sleep again. He discovered

when he turned out in the morning that the tussock-grass

which we had laid on the floor of the cave had smouldered

outwards from the fire and had actually burned a large hole

in the bag beneath his feet. Fortunately, his feet were

not harmed.

- During the morning of this day (May 13) Worsley

and I tramped across the hills in a north-easterly

direction with the object of getting a view of the sound

and possibly gathering some information that would be useful

to us in the next stage of our journey. It was exhausting

work, but after covering about 2 and a half miles in two

hours, we were able to look east, up the bay. We could not

see very much of the country that we would have to cross

in order to reach the whaling-station on the other side

of the island. We had passed several brooks and frozen tarns,

and at a point where we had to take to the beach on the

shore of the sound we found some wreckage, an 18-ft. pine-spar

(probably part of a ship's topmast), several pieces of timber,

and a little model of a ship's hull, evidently a child's

toy. We wondered what tragedy that pitiful little plaything

indicated. We encountered also some gentoo penguins and

a young sea-elephant, which Worsley killed.

- A fresh west-south-westerly breeze was blowing on the

following morning (Wednesday, May 17), with misty squalls,

sleet, and rain. I took Worsley with me

on a pioneer journey to the west with the object of examining

the country to be traversed at the beginning of the overland

journey. We went round the seaward end of the snouted glacier,

and after tramping about a mile over stony ground and snow-coated

debris, we crossed some big ridges of scree and moraines.

We found that there was good going for a sledge as far as

the north-east corner of the bay, but did not get much information

regarding the conditions farther on owing to the view becoming

obscured by a snow-squall. We waited a quarter of an hour

for the weather to clear but were forced to turn back without

having seen more of the country. I had satisfied myself,

however, that we could reach a good snow-slope leading apparently

to the inland ice. Worsley reckoned from

the chart that the distance from our camp to Husvik, on

an east magnetic course, was seventeen geographical miles,

but we could not expect to follow a direct line. The carpenter

started making a sledge for use on the overland journey.

The materials at his disposal were limited in quantity and

scarcely suitable in quality.

- We overhauled our gear on Thursday, May 18; and hauled our sledge to the lower edge of the snouted glacier. The vehicle proved heavy and cumbrous. We had to lift it empty over bare patches of rock along the shore, and I realized that it would be too heavy for three men to manage amid the snow-plains, glaciers, and peaks of the interior. Worsley and Crean were coming with me, and after consultation we decided to leave the sleeping-bags behind us and make the journey in very light marching order. We would take three days' provisions for each man in the form of sledging ration and biscuit. The food was to be packed in three sacks, so that each member of the party could carry his own supply. Then we were to take the Primus lamp filled with oil, the small cooker, the carpenter's adze (for use as an ice-axe), and the alpine rope, which made a total length of fifty feet when knotted. We might have to lower ourselves down steep slopes or cross crevassed glaciers. The filled lamp would provide six hot meals, which would consist of sledging ration boiled up with biscuit. There were two boxes of matches left, one full and the other partially used. We left the full box with the men at the camp and took the second box, which contained forty-eight matches. I was unfortunate as regarded footgear, since I had given away my heavy Burberry boots on the floe, and had now a comparatively light pair in poor condition. The carpenter assisted me by putting several screws in the sole of each boot with the object of providing a grip on the ice. The screws came out of the James Caird.

Landmarks named after Frank Arthur Worsley

Feature Name: Worsley IcefallsFeature Type: Class: Glacier

Latitude: 82°57'00''S

Longitude: 155°00'00''E

Description: Icefalls near the head of Nimrod Glacier.

Feature Name: Mount Worsley

Feature Type: Summit

Latitude:

54°11'00''S

Longitude: 037°09'00''W

Description: Mountain, 1,105 m, on the

W side of Briggs Glacier in South Georgia.

Elevation(

ft/m ): 3625 / 1105

Feature Name: Cape Worsley

Feature Type: Cape

Latitude:

64°39'00''S

Longitude:060°24'00''W

Description: Dome-shaped cape 225 m high

with snow-free cliffs on the S and E sides, lying 10 mi E of

the S end of Detroit Plateau on the E coast of Graham Land.

Elevation( ft/m ): 738 / 225

Other Crew of the Endurance Expedition

Bakewell,

William - Able Seaman

Blackborow,

Percy - Stowaway (later steward)

Cheetham,

Alfred - Third Officer

Clark, Robert S.

- Biologist

Crean, Thomas

- Second Officer

Green, Charles J.

- Cook

Greenstreet,

Lionel - First Officer

Holness, Ernest

- Fireman/stoker

How, Walter E.

- Able Seaman

Hudson, Hubert T.

- Navigator

Hurley, James Francis

(Frank) - Official Photographer

Hussey,

Leonard D. A. - Meteorologist

James,

Reginald W. - Physicist

Kerr, Alexander.

J. - Second Engineer

Macklin,

Dr. Alexander H. - Surgeon

Marston,

George E. - Official Artist

McCarthy, Timothy

- Able Seaman

McIlroy, Dr. James

A. - Surgeon

McLeod, Thomas

- Able Seaman

McNish, Henry

- Carpenter

Orde-Lees, Thomas

- Motor Expert and Storekeeper

Rickinson, Lewis

- First Engineer

Shackleton,

Ernest H. - Expedition Leader

Stephenson,

William - Fireman/stoker

Vincent, John

- Able Seaman

Wild, Frank

- Second in Command

Wordie, James M.

- Geologist

Worsley, Frank

- Captain

Biographical information

- I am concentrating on the Polar experiences of the men involved.

Any further information or pictures visitors may have will be gratefully received.

Please email

- Paul Ward, webmaster.

What are the chances that my ancestor was an unsung part of the Heroic Age

of Antarctic Exploration?

Ernest Shackleton Books and Video

South - Ernest Shackleton and the Endurance Expedition (1919)

original footage - DVD

Shackleton

dramatization

Kenneth Branagh (2002) - DVD

Shackleton's Antarctic Adventure (2001)

IMAX dramatization - DVD

The Endurance - Shackleton's Legendary Expedition (2000)

PBS NOVA, dramatization with original footage - DVD

Endurance : Shackleton's Incredible Voyage

Alfred Lansing (Preface) - Book

South with Endurance: Frank Hurley - official photographer

Book

South! Ernest Shackleton Shackleton's own words

Book

Shackleton's Way: Leadership Lessons from the Great Antarctic Explorer

Book