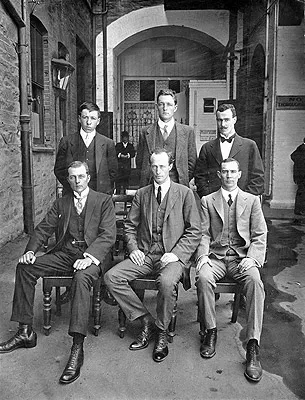

Francis H. Bickerton F.R.G.S.

Biographical Notes

In charge of air-tractor sledge - Aurora 1911-1913

Single, born in Oxford, England. Had studied engineering:

joined the Expedition as Electrical Engineer and Motor Expert.

A member of the Main Base Party and leader of the Western Sledging

Party, he remained in the Antarctic for two years, during which

time he was in charge of the air-tractor sledge, and was engineer

to the wireless station. For a time, during the second year,

he was in complete charge of the wireless plant.

From

Appendix 1, Mawson - Heart of the Antarctic

Bickerton was a larger than life figure who engaged in numerous adventures, even before his trip with Mawson, he had returned recently from a trip looking for buried treasure on a lonely Pacific island.

For a short biography of his later life see here

Bickerton farmed in British Nyasaland in the neighbourhood of Lake Nyasa (South Africa) with his friend Frank Wild - Shackleton's second-in-command and Dr. James McIlroy between the end of the First World War and Wild and McIlroy leaving to join the "Quest" expedition in 1921. They cleared the then virgin forest and planted cotton.

Letter sent by Frank Wild from South Africa to his Cousin Margaret, 4th August 1920

Landmarks named after F. H. Bickerton

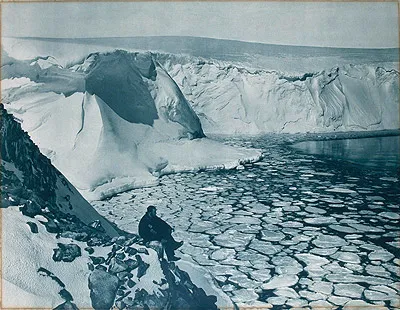

Feature Name: Cape Bickerton

Feature Type: cape

Latitude: 6620S

Longitude: 13656E

Description: Ice-covered point

5 mi ENE of Gravenoire Rock which marks the N extremity of the

coastal area close E of Victor Bay. Charted by the AAE under

Mawson, 1911-14, and named by him for F. H. Bickerton, engineer

of the expedition and leader of the Western Party which sighted

the cape from its farthest west camp.

Variant Name

- Cape Richardson

References to Francis

Bickerton in Mawson's book "The Home of the Blizzard"

buy USA |

buy UK

-

This machine was originally an R.E.P. monoplane, constructed by Messrs. Vickers and Co., but supplied with a special detachable, sledge-runner undercarriage for use in the Antarctic, converting it into a tractor for hauling sledges. It was intended that so far as its role as a flier was concerned, it would be chiefly exercised for the purpose of drawing public attention to the Expedition in Australia, where aviation was then almost unknown. With this object in view, it arrived in Adelaide at an early date accompanied by the aviator, Lieutenant Watkins, assisted by Bickerton. There it unfortunately came to grief, and Watkins and Wild narrowly escaped death in the accident. It was then decided to make no attempt to fly in the Antarctic; the wings were left in Australia and Lieutenant Watkins returned to England. In the meantime, the machine was repaired and forwarded to Hobart.

-

Each mast, of oregon timber, was in four sections. The lowest section was ten inches square and tapered upwards to the small royal mast at a prospective height of one hundred and twenty feet. At an early stage it was realized that we could not expect to erect more than three sections. Round the steel caps at each doubling a good deal of fitting had to be done, and Bickerton, in such occupation, spent many hours aloft throughout the year. Fumbling with bulky mitts, handling hammers and spanners, and manipulating nuts and bolts with bare hands, while suspended in a boatswain's chair in the wind, the man up the mast had a difficult and miserable task. Bickerton was the hero of all such endeavours. Hannam directed the other workers who steadied the stays, cleared or made fast the ropes, pulled and stood by the hauling tackle and so forth.

-

Six days after this accident, August 17, the top-mast halliard of the down-wind mast frayed through, and as a stronger block was to be affixed for the aerial, some one had to climb up to wire it in position. Bickerton improvized a pair of climbing irons, and, after some preliminary practice, ascended in fine style.

-

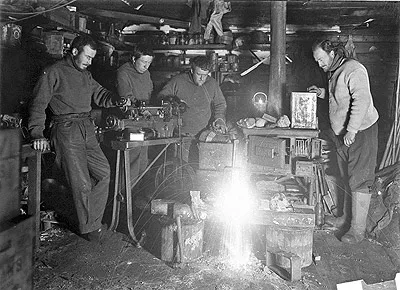

Meanwhile, other occupations were in full swing. An amateur cobbler, his crampon on a last, studded its spiked surface with clouts, hammering away in complete disregard of the night-watchman's uneasy slumbers. The big sewing-machine raced at top-speed round the flounce of a tent, and in odd corners among the bunks were groups mending mitts, strengthening sleeping-bags and patching burberrys. The cartographer at his table beneath a shaded acetylene light drew maps and sketched, the magnetician was busy on calculations close by. The cook and messman often made their presence felt and heard. In the outer Hut, the lathe spun round, its whirr and click drowned in the noisy rasp of the grinder and the blast of the big blow-lamp. The last-named, Bickerton, "bus-driver" and air-tractor expert, had converted, with the aid of a few pieces of covering tin, into a forge. A piece of red-hot metal was lifted out and thrust into the vice; Hannam was striker and Bickerton holder. General conversation was conducted in shouts, Hannam's being easily predominant.

-

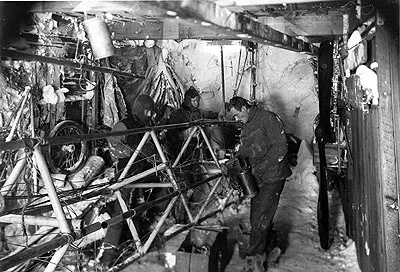

On all but the worst days a gang of men worked with picks and shovels digging out the Hangar, so that Bickerton could test the air-tractor sledge. The attack was concentrated upon a solid bank of snow and ice into which heaps of tins and rubbish had been compactly frozen. In soft snow enormous headway can be made in a short space of time, but in that species of conglomerate, progress is slow. Eventually, a cutting was made by which the machine could pass out. The rampart of snow was broken through at the northern end of the Hangar, and the sledge with its long curved runners was hauled forth triumphantly on the 25th. From that time onwards Bickerton continued to experiment and to improve the contrivance.

-

A redistribution of parties and duties was made. Hodgeman joined Whetter and Bickerton in preparation for the air-tractor sledge's trip to the west. Hunter took up the position of meteorologist and devoted all his spare time to biological investigations amongst the immigrant life of summer. Hannam continued to act as magnetician and general "handy man." Murphy, who was also to be in charge during the summer, returned to his stores, making preparations for departure. Hourly meteorological observations kept every one vigilant at the Hut.

-

It was now a common thing for those of us who had gone to bed before midnight to wake up in the morning and find that quite a budget of wireless messages had been received. It took the place of a morning paper and we made the most of the intelligence, discussing it from every possible point of view. Jeffryes and Bickerton worked every night from 8 P.M. until 1 A.M., calling at short intervals and listening attentively at the receiver. In fact, notes were kept of the intensity of the signals, the presence of local atmospheric electrical discharges - "static" - or intermittent sounds due to discharges from snow particles - St. Elmo's fire - and, lastly, of interference in the signals transmitted. The latter phenomenon should lead to interesting deductions, for we had frequent evidence to show that the wireless waves were greatly impeded or completely abolished during times of auroral activity.

-

This notice was to the effect that the non-arrival of the leader's party rendered it necessary to prepare for the establishment of a relief expedition at Winter Quarters and appointed Bage, Bickerton, Hodgeman, Jeffryes and McLean as members, under the command of Madigan; to remain in Antarctica for another year if necessary.

-

Meanwhile, it was suggested that if a heavy kite were made and induced to fly in the continuous winds, the aerial thus provided would be sufficient to receive wireless messages. To this end, Bage and Bickerton set to work, and the first invention was a Venesta-box kite which was tried in a steady seventy-mile wind. Despite its weight - at least ten pounds - the kite rose immediately, steadied by guys on either side, and then suddenly descended with a crash on to the glacier ice. After the third fall the kite was too battered to be of any further use. Another device, in which an empty carbide tin was employed, and still another, making use of an old propeller, shared the same fate.

Biographical information

- I am concentrating on the Polar experiences of the men involved.

Any further information or pictures visitors may have will be gratefully received.

Please email

- Paul Ward, webmaster.

What are the chances that my ancestor was an unsung part of the Heroic Age

of Antarctic Exploration?