Emperor Penguins - Aptenodytes forsteri

Facts, Biology and Adaptations

Emperor penguins have the upright and regal bearing that their name suggests. They take the dinner-jacketed formality of all penguins to its highest level and though they are able to be as awkward, gawky and get as dirty as other penguins, when they shake it all off and stand up to regain their dignity, there are few if any, more stately and elegant animals on earth.

Emperor Penguin Basics

Average Weight: 30kg - 66lb

Average Height: 115cm - 3.8ft

Breeding Season: April - December -

Emperors breed in the depth of the Antarctic winter. The

average temperature is around -20°C (-4°F) falling

as low as -50°C (- 58°F) and with winds that gust

up to 200km per hour (124mph).

Reproduction:

Emperor Penguins breed almost exclusively on sea-ice near

to the coast of Antarctica, rarely on land, the breeding

colonies can be up to 200 km from the open sea.

Estimated world population: - 595,000,

stable.

Diet and Feeding: Emperor

penguins eat mainly fish in Antarctica, krill and squid

are also important parts of their diet, the relative importance

of these three depend on the area they live in and what

is available at the time.

Conservation status:

Near threatened..

Distribution:

Circumpolar, breed right up against the continent.

Predators: Leopard seals and killer

whales are the main predators of adult birds, skuas prey

on eggs and chicks.

What are Emperor penguins like?

Emperor penguins are the largest of all penguin species with an average weight of around 30kg (66lb) but can be up to 40kg (88lb) and a height of approx. 1.15m (3.8ft).

They have colourful feathers around their necks and heads, though are not quite as bright as king penguins which are almost as large. There is little or no possibility of confusing the two species however as their distribution around Antarctica is very different. While king penguins are a sub-Antarctic species, being based on islands dotted around the continent, emperor penguins are animals of the deep south. They are never found together.

Emperor penguins have yellow ear patches that are "open" fading into the white of the breast feathers, whereas king penguins have orange ear patches that are "closed" by a band of black feathers. Emperor penguin chicks have distinctive plumage with a large white face patch.

Where do Emperor penguins live?

All but 3 of about 40 known emperor penguin colonies are on winter fast ice that is frozen solid and attached to the land from autumn until it begins to break up in the spring (though some years it doesn't break up at all). They are found all around the coasts of the Antarctic continent. They breed during the depths of the Antarctic winter and in some of the most desolate, coldest, windiest and downright grim places on the planet during the season of 24 hour darkness. Some emperor penguins are the only birds that never set foot on land.

The first breeding colony wasn't discovered until 1902 by Lt. Reginald Skelton on Scott's 1901-04 Discovery Expedition some 130 years after the birds had first been seen on Captain Cook's second voyage. New colonies were still being discovered as late as 2009. Nowadays satellite imagery is used to find breeding emperor penguin colonies in remote regions.

Early in the 20th century, Emperor penguins were thought to be some kind of evolutionary "missing link", something that scientists thought could be proven by observing the growth of the embryo at various stages. On Scott's 1910-1913 Terra Nova expedition a small group of expeditioners set out on a winter sledging journey led by Wilson, the biologist and including the young Apsley Cherry-Garrard, famously this gave rise to the acknowledged greatest of all Antarctic adventure and travel books "The Worst Journey in the World".

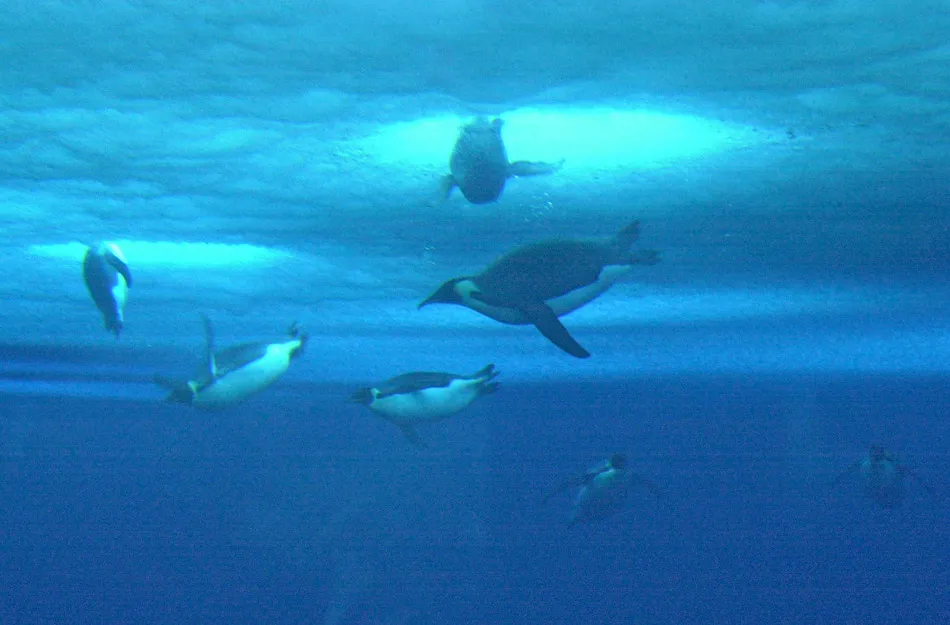

Emperor penguin diving adaptations

Emperor penguins feed on fish, krill and squid which they catch on dives that are longer and deeper than any other penguin or bird species. They can dive to a depth of 1,800 feet (550 meters) and hold their breath for up to 22 minutes. This allows them to reach and exploit food resources that other birds can't reach.

The diving adaptations and abilities of emperor penguins have been widely studied, they have been found to have:

1/ an increased ability to store oxygen in the body

2/ the ability to tolerate low levels of oxygen in the body

3/ the ability to tolerate the effects of pressure.

Emperor penguins tolerate low levels of oxygen during dives that would cause a human to pass out and they experience pressures so great that we would get the bends. Neither of these things seem to adversely affect penguins. Their diving physiology is studied at McMurdo Station at a place called penguin ranch 15 miles out in the sea ice where there is only a single hole in the ice, so the penguins must return there to leave the sea.

A penguin's normal resting heart-beat is about 60-70 beats per minute (bpm), this goes up to 180-200 bpm before a dive as they load up with oxygen, then as they hit the water, the rate drops to 100 bpm immediately slowing to only 20 bpm during most of the dive so they use the stored oxygen in blood and muscles to the maximum effect. On returning to the surface again, the heart rate goes back to 200 bpm probably to pay back the "oxygen debt" they have incurred during the dive.

What is unusual about the Emperor Penguins breeding cycle?

Emperor penguins breed almost exclusively on sea ice and so are perhaps the only species of bird that never sets foot on land.

They begin their breeding cycle when other Antarctic penguins have finished theirs, at the end of April to May. Other smaller penguins at this time head north away from the encroaching winter while the Emperors head south into it. They seem to choose very dramatic sites, a large flat area where they can waddle when carrying their egg or chick on their feet surrounded by high ice cliffs or icebergs that help to give a little shelter from the winds.

Eggs are laid in May and June, they are the smallest egg relative to body size of any bird, being around 0.4kg (1.1lb) just under 1.5% of the mass of an adult bird.

At this point, the males take charge of the egg. No nest is built and the egg is incubated on the feet of the parents, a special fold of abdominal skin covers the egg to keep it warm. The mother penguins then set off back to sea and do not return for nearly four months.

The male Emperors with their valuable eggs sit huddled together on the ice throughout the dark months of the Antarctic night. The average temperature is around -20°C (-4°F) going down to -50°C (- 58°F) and with winds that gust up to 200km per hour (124mph). The males do not eat at all throughout this time, but just sit and wait and protect their egg (later the chick) until their mate comes back to relieve them.

Very few people have seen an emperor penguin huddle in the winter in savage places ruled by ice and cold, the penguins spend their days largely in silence. The only events are changing position in the huddle (see below) and the immense spectacle of the ghostly red, violet and green of the southern lights or Aurora Australis sometimes playing in the dark skies above their heads.

Males sit incubating the egg, waiting for an average of 115 days and up to 120, during this time they will lose about 40% of their body weight. They use less energy when asleep which they do so as long as possible, it is not unusual for emperor penguins to sleep for 20 or more hours a day under these conditions - even up to 24 hours a day, to conserve their food supplies and increase their and their chick's chances of survival.

They survive by huddling together for warmth, very unusual behaviour for adults of other penguin species which are usually aggressively territorial. They also take it in turns to occupy the coldest most exposed outside positions.

Without this huddling behaviour, they would unable to endure the combined conditions of fasting, bitter cold and hurricane force winds and would not be able to live and breed in the way they do.

Even though they are close together during these huddles, they have been recently shown to be not quite touching. if they touched and squashed the puffed out feathers down it would reduce the insulating value and make them colder, so they really fine-tune the process.

It's not all altruistic behaviour taking it in turns though. The ones that have been on the outside on the windward side wander off to the leeward side when they've had enough so exposing the next "layer" of penguins. The whole huddle can wander over quite an area in this way in prolonged very cold and windy conditions.

How does the chick survive when born on the open sea ice?

Eventually, the female returns across the sea ice. This usually coincides with the hatching of the chick. Sometimes the chick will hatch before the female returns, if this happens, it will be fed with a secretion of protein and fat produced by the male from its oesophagus a sort of penguin "milk".

The pair locate each other by calling repeatedly, eventually recognizing each others voice, and the male passes the chick over (sometimes reluctantly and after much persuasion) onto the feet of the female. A chick left alone on the ice at this time has a survival time of only around two minutes. The males are then able to go off to sea to feed and build up their strength and fitness again. This journey alone can take several days across the ice. Emperor penguins have been known to walk 280km to reach the sea.

As the chicks grow older and get larger, they become able to regulate their own temperature in milder conditions, so they don't need the protection of the brood patch. They form chick-only groups called creches and will huddle as the parents do if the weather worsens. At this point, the chick is reared in the conventional penguin manner, with the parents taking it in turns to feed and look after the chick until they are large enough to leave.

Chick survival has a lot to do with how the ice breaks up and so how easy it is for parents to reach the sea. If the parents have to travel long distances, many chicks will die of starvation. If the ice edge remains close, then the parents will be able to provide more food and the chicks stand a better chance of survival. Sometimes the sea-ice may break up while the chicks still have their juvenile down leading to a high mortality as they are unable to keep warm in the sea without adult feathers.

The colonies begin to disperse as the sea ice begins to break up in December and January, the chicks are then able to fend for themselves leaving the adults to moult their feathers (a time when they need to stay out of the water) and so are not able to feed.

Why do emperor penguins breed in such severe conditions?

Despite appearances, this breeding strategy of the emperor penguin does make sense. Emperors are large birds, twice the weight of the next biggest penguin, the king, and so are able to survive the winter fast and the extreme cold temperatures endured at this time.

The chicks are very large too compared to other penguin species, if they were reared in the summer, they would have to be left to fend for themselves at a time of the year when food supply is reducing. As the chicks food requirement is very high, this would cause major problems.

This breeding strategy means the penguin chicks are born early and become independent during the height of the abundant summer food supply giving them time to grow and fatten up for the following winter.

Emperor penguins are able to raise a chick each year by this strategy, though the rigorous conditions of life in the deep south mean that only 19% of chicks will survive their first year.

Emperors are preyed upon by Killer Whales, Leopard Seals, and the Giant Petrel. The most dangerous predator is the Leopard Seal that can eat about 15 penguins a day though they usually only catch the weak or the very sick. Healthy penguins can usually out-swim a Leopard Seal.

There were estimated to be around 238,000 breeding pairs of emperor penguins in the world in 2009. Taking into consideration the non-breeder ratio as well this translates into about 595,000 adult birds. Emperor penguins reach breeding age at 4 years and can live to be 20.

Emperor penguin adaptations

Of all animals on earth, the Emperor Penguin has a claim on being one that endures some of the most extreme conditions. To do this they have many adaptations that can be categorized as follows:

- Anatomical - Structures of the body.

- Behavioural - The manner in which animals move and act.

- Physiological - The internal functions of the animal from biochemical, to cellular, tissue, organ and whole organism levels.

Emperor Penguin Anatomical Adaptations

- Large size - helps

to retain heat, Emperors are twice the size of the next

biggest penguin, they are able to survive the extreme cold

temperatures of winter without feeding for extended periods.

A large size, with low surface to area ratio slows down

the loss of heat, a simple shape and flippers that can be

held close to the body also reduce surface area on land.

- Short stiff tail - on land the tail

forms a tripod when the penguin rocks back slightly on its

heels, this gives the minimum contact area with the ice

or snow to prevent heat loss.

- Chicks have soft down for insulation,

this is a more effective insulator on land than

the feathers that the adult birds have, but are of little

use in the sea, they must moult and grow feathers before

they can swim.

- Highly specialized bird skeleton a

very upright gait, short neck, short legs and long body.

- Powerful claws on the feet to help to gain a grip on snow, ice or rock when emerging from the ocean or when tobogganing.

Emperor Penguin Behavioural Adaptations

- Huddle together to conserve heat, without

this behaviour they wouldn't be able to survive the

Antarctic winter. The penguins shield each other from the

wind by taking it in turns to be on the outside or inside

of the huddle, they stand very close to each other but don't

actually touch in order to get the maximum insulation from

their own feathers and those of the penguins around them.

- Unlike other penguin species, they are not aggressively

territorial, this allows for huddling to take place.

- No nest is made, the eggs and then chicks sit

on the parents feet to keep them off the ice, they

are covered by a fold of skin to keep them warm and are

carefully moved from one parent to the other when they are

small to allow the parents to take turns to go fishing.

- They breed during the depths of the Antarctic

winter, so the chicks are large enough to become

independent during the summer abundance of food, other smaller

penguin species are able to grow quickly enough when breeding

in the spring.

- Males will sleep for 20-24 hours a day while

incubating the egg and waiting for the female to return,

this conserves energy.

- When the female lays her egg, it is passed over

to the male, the female then goes to sea and will

not return for an average of 115 days but up to 120.

Emperor Penguin Physiological Adaptations

- A complex heat exchange system that

allows 80% of heat in the breath to be recaptured in the

nasal passages.

- Heat exchange systems in the flippers and legs

keep these regions cooler than the body core and

prevent what otherwise would be a disproportionate heat

loss from these areas.

- They can dive to a depth of 1,800 feet (550

meters) and hold their breath for up to 22 minutes,

so are able to reach and exploit food resources

that other birds can't reach.

- The normal resting heart-beat is about

60-70 beats per minute (bpm), this goes up to 180-200 bpm

before a dive as they load up with oxygen, as they hit the

water, the rate drops to 100 bpm immediately, slowing to

20 bpm for most of the dive.

- Males can make "milk" in

the oesophagus which can be used to feed chicks in the winter

before the female arrives back from fishing.

- Males can fast for over 100 days while incubating the egg and awaiting the return of the females.

Pictures used courtesy of Warner Brothers or NOAA